What a Canadian experiment tells us about cash transfers and homelessness

35,000 Canadians experience homelessness each night, violating their right to adequate housing and threatening their health, safety and access to education. The Covid-19 pandemic exacerbates the issue, given crowded living conditions and comorbidities, and the Canadian government has taken new steps to address it, such as moving people experiencing homelessness into hotels.

Prior to the pandemic, a Vancouver nonprofit, Foundations for Social Change, worked with the University of British Columbia to test a novel homelessness intervention: unconditional cash transfers. In spring 2018, their New Leaf Project (NLP) granted a lump sum cash transfer to Lower Mainland residents experiencing homelessness, and compared their outcomes to a control group. While some questions remain, the findings reveal that unconditional cash transfers, which are otherwise shown to improve health, education, and other outcomes, offer potential to reduce homelessness.

Study overview

NLP selected 115 long-term residents or citizens of Canada aged 19 to 64 who had experienced homelessness within the previous six months. This group is fairly representative of Canada’s homeless population, given only about 10 percent of people experiencing homelessness in a year were homeless for more than a month, and about four percent are aged 65 or older. People with severe substance abuse or mental health disorders were ineligible for NLP.

At the beginning of the experiment, NLP deposited CAD 7,5001 into the bank accounts of 50 participants, randomly selected from the full group of 115. Each cash recipient was also provided access to workshops, and 25 also had access to coaching. Of the 65 who did not receive cash, 19 were provided access to workshops and coaching, while the other 46 were not.2 Workshops focused on the development of a personal financial plan and self-affirmation exercises, and the coaching was offered for six months, aiming to develop and sustain life skills and strategies. Researchers tracked participants over twelve months, filling out questionnaires at one, three, six, nine and twelve months and open-ended qualitative interviews at six and twelve months.

Results

Spending

The cash group spent an average of CAD 426 per month more than the non cash group over the course of the year. This amounts to 42 percent more than the non-cash group, or 6 percent of the total CAD 7,500 lump sum transfer. This extra spending covered a diverse range of categories: 54 percent more on transit, 113 percent more on clothing, 34 percent more on food, and so on. Of the treatment groups, the cash group increased its expenditure on alcohol, drugs, and cigarettes by the smallest proportion (11 percent).3 It also increased its expenditure on food and clothing for the children of recipients by the largest proportion (171 percent).

Another way of quantifying the changes is as a share of spending. Alcohol, drugs, and cigarettes made up 9 percent of the cash group’s spending, a fifth less than the non-cash group’s 11.4 percent, while food and clothes for children made up 7.9 percent of the cash group’s spending, nearly double the 4.1 percent share in the non-cash group. The cash group also spent a larger share on clothes (for themselves) and transit, and a smaller share on rent and food.

Transitions to stable housing

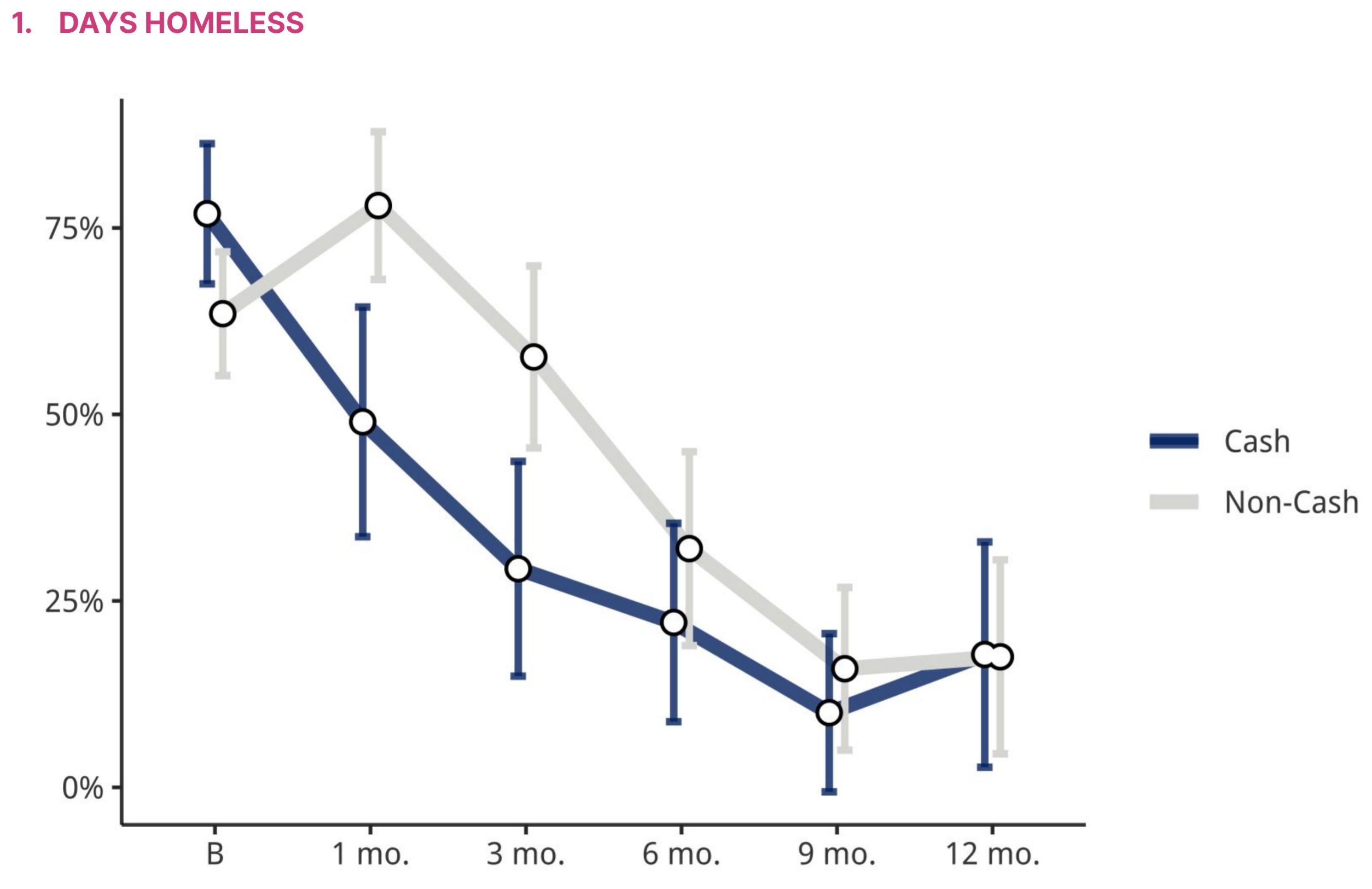

Cash recipients also spent less time homeless than the control group. The two groups started similarly, but in the month following the intervention, the cash group was only homeless for 49 percent of days, while the control group was homeless for 78 percent of those days. The effect diminished over time, and by the end of the year, the two groups converged at around a fifth of days homeless. Overall, people in the cash group spent an average of 88 fewer days homeless throughout the full year.

Those extra 88 days in homelessness housing and services would have cost the government about $8,200, exceeding the $7,500 grant (NLP did not report total costs beyond the grant, which would factor into a comprehensive cost-effectiveness analysis).

In open-ended surveys, cash recipients reported that they did not have to depend on social services and could move into housing that better met their preferences. For instance, one participant said, “The impact it had on my life was huge. I was able to do a lot of things that I couldn’t do before. It has changed my ability to make proper choices. If I had not received the cash transfer, I wouldn’t be able to move out. Wouldn’t be able to get my car back on the road. None of that.”

Comparison with other studies

While NLP is the first randomized controlled trial giving unconditional cash transfers to people experiencing homelessness, it aligns with other studies on how cash transfers are spent.

The diversity of NLP participants’ spending is not unusual. The NGO GiveDirectly, which distributes unconditional cash transfers to extremely poor households in East Africa, found in a randomized controlled trial that “With the exception of temptation goods (alcohol and tobacco), transfers increase expenditures in all categories, including food, medical and education expenditure, and social events.” GiveDirectly’s GDLive tool shows unfiltered, unedited stories from recipients of their unconditional cash transfers and universal basic income payments; perusing the stories of UBI recipients reveals variety in spending, from poultry and tea seedlings to school fees and dowries to water tanks and homebuilding materials. A study of Australia’s Covid-19 economic support payment also found that recipients—mostly pensioners—increased spending across a diverse range of categories. Given many in-kind assistance programs target just one or two categories each, such as food and rent, cash can fill in gaps for other needs that might be harder for policymakers to anticipate.

Spending on children is especially common, as evidenced by the robust evidence that cash transfers benefit children. As we summarize in our child allowance paper, cash transfers consistently improve education and nutrition, as well as long-term outcomes like earnings and even lifespan, across both developing and developed countries. One study from Canada found that when Manitoba increased its child benefit in 2001, children ages 0 to 3 showed improved motor and social development, children ages 4-5 showed lower aggression and anxiety.

A common concern around giving money to poor people is that they will spend on temptation goods like alcohol, drugs, and cigarettes. This worry motivated San Francisco voters to replace cash assistance for people experiencing homelessness with in-kind benefits like housing, in a 2002 program called “Care Not Cash.” A number of studies show such concerns to be misplaced. Data from San Francisco’s pre-Care-Not-Cash days indicates that homeless cash recipients were less likely to use drugs than those who didn’t receive cash (they were also less likely to receive income from selling drugs or be incarcerated, and more likely to find shelter). A 2015 Gallup poll and a 2011 analysis of the Panel Study of Income Dynamics also found that low-income people consume less alcohol than higher-income people (though they’re more likely to drink heavy quantities and similarly likely to report that they drink more than they should). A 2014 World Bank meta-analysis demonstrates that these results are not mere correlations: data from 19 quantitative papers, including several randomized controlled trials, found that cash transfers most often reduced or had no effect on temptation good consumption.4

Conclusion

Canada has long welcomed unconditional cash transfers, from the 1970s “Mincome” program in Manitoba to its unusually generous child benefit to its prematurely-cancelled basic income pilot in Ontario. And as developed and developing countries tackle homelessness, discussions inevitably include cash, whether it’s San Francisco retracting cash assistance in 2002 or Manila introducing a conditional cash transfer in 2012.

NLP unites Canadian interest in cash transfers with homelessness research. It shows that people experiencing homelessness spread lump-sum transfers over time and across spending categories—especially focusing on their children—and that cash transfers accelerate transitions into stable housing.

Some questions following this study remain. For example, how would cash transfers affect the 40 percent of Canadians experiencing homelessness who have substance abuse disorders? Or the similar share with mental illness? NLP excluded both groups from this round, though a recent Science meta-review found that “cash transfers and broader anti-poverty programs reduce depression and anxiety in randomized trials.” The long-term effects on children experiencing homelessness may be even starker, as the review also finds that “poverty experienced in childhood and in utero [results] in impaired cognitive development and adult mental illness.”

Another question is: how do lump sum transfers, as used in the NLP experiment, compare to recurring payments for people experiencing homelessness? Research to date on this question has largely focused on developing countries. For example, a review of post-emergency aid and development contexts suggests that regular payments are less prone to corruption than lump sum transfers, and that they outperform on measures of social protection, while lump-sum transfers can more effectively spur investment if targeted to entrepreneurs. Similarly, a GiveDirectly study among poor households in rural Kenya found: “Monthly transfers are more likely than lump-sum transfers to improve food security, whereas lump-sum transfers are more likely to be spent on durables,” and forthcoming results from its basic income experiment will shed more light on the topic.

Beyond helping people currently experiencing homelessness, how can cash transfers prevent homelessness? Studies from UCLA and Zillow link housing affordability and homelessness, suggesting that (along with reducing housing costs) raising incomes via cash transfers could keep people housed.

Finally: how much of these effects can be attributed to cash transfers compared to coaching, workshops, and other overhead, and how do these other costs affect cost-benefit analysis? This first experimental design makes it difficult to disentangle effects, but future experiments could omit other components to focus on the cash transfer, or test other components in a grid or hierarchical design. For example, a recent study on psychological well-being in rural Kenya employed a two-by-two experimental design to study the effect of cash transfers, a psychotherapy program, and the combination of the two. This revealed that, while the cash transfer improved well-being, psychotherapy did not—either by itself or in conjunction with the cash. A similar approach could quantify the effect of coaching or workshops, conditional on cash transfers.

Foundations for Social Change has committed to publishing a peer-reviewed paper on this round of results, and they are raising $10 million to enroll more participants across more Canadian cities and expand research capacity. Any follow-up research is likely to improve the precision of these estimates on expenditures and housing stability, and quantify the external validity to new contexts, even if only geographic. Open questions on cash and homelessness makes this fertile ground for further research, whether from NLP or other organizations. If nothing else, this study suggests that expanding cash assistance will increase spending on diverse needs—especially of children—and accelerate transitions to stable housing, thereby improving the range of outcomes associated with homelessness.

-

CAD 7,500 is equivalent to about USD 5,900 as of December 2020. ↩

-

Researchers did not explain their choice to have unbalanced treatment and control groups, or to give workshop access only to the cash group. ↩

-

The study claims a “39% reduction in spending on alcohol, cigarettes and drugs.” In email correspondence, Foundations for Social Change clarified that this is a comparison of pre-pilot spending with that at the end of 12 months for the cash group (i.e. not compared to the non-cash group). ↩

-

Temptation goods are defined as: “goods that generate positive utility for the self that consumes them, but not for any previous self that anticipates that they will be consumed in the future.” But the meta study focuses principally on alcohol and tobacco. Similarly, the study suggests that temptation goods are synonymous with demerit goods or, “goods that were so demeritorious (either to the consumer or to others) that the government may be correct in regulating their use. That term is sometimes used in reference to alcohol and tobacco in cash transfer studies.” ↩

Subscribe to the UBI Center

Get the latest posts delivered right to your inbox